Supreme Court struck down the Centre’s orders on retrospective green clearances

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 19th May 2025 Home / Supreme Court struck down the Centre’s orders on retrospective green clearances Why in News? The Supreme Court struck down the 2017 MoEF&CC notification and 2021 SOP allowing post-facto environmental clearances, declaring them unconstitutional for violating the right to a healthy environment under Article 21. Key Highlights Recently, the Supreme Court of India struck down a 2017 notification issued by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF&CC), which allowed post facto environmental clearances for industrial projects that had commenced operations without prior approval. The Court also invalidated the 2021 office memorandum (OM) that institutionalized a standard operating procedure (SOP) for handling such cases. Background: The Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006, mandates prior environmental clearance before the commencement of any project with potential environmental impacts. The clearance involves multi-stage scrutiny, including: Screening and scoping of the project Impact assessment Public hearing Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) recommendations Despite this, in March 2017, the MoEF&CC issued a notification allowing a “one-time” six-month window for industries to obtain post facto clearance, even if they had already violated the EIA norms by beginning operations or modifying existing projects. Rationale Behind the 2017 Notification: Regulatory Compliance: The Centre argued that it was better to bring violators under the environmental regulatory net rather than leaving violations unregulated. Remediation Costs: Violators would be compelled to pay for remediation and pollution damage, nullifying any economic advantage gained through non-compliance. Centralized Appraisal: All violation cases, regardless of scale, were to be appraised centrally. Closure Clause: Only activities permissible at the site would be allowed to proceed; others faced closure. Supreme Court’s Judgment: A bench of Justice Abhay S. Oka and Justice Ujjal Bhuyan declared: The 2017 notification and 2021 OM are illegal and violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. The right to a clean and pollution-free environment is part of the right to life under Article 21. Post facto clearance undermines environmental law and encourages illegal project execution. The Court restrained the Centre from issuing any future notifications or memoranda similar in intent or effect. Violation of Judicial Precedents: The Court cited two key judgments: Common Cause v. Union of India (2017) Alembic Pharmaceuticals v. Rohit Prajapati (2020) Both judgments held that ex-post facto clearances are contrary to environmental jurisprudence and cannot be allowed as they defeat the preventive intent of EIA norms. Criticism of the Centre’s Approach: The Court criticized the Centre for protecting violators instead of upholding environmental laws. It noted that in the Alembic case, even a one-time amnesty was considered illegal. The 2021 SOP, although not using the term post facto, was seen as an indirect attempt to regularize violations, which the Court found unacceptable. Key Constitutional Principles Upheld: Article 21: Right to life includes the right to a healthy environment. Article 14: Equal treatment under law; violators cannot be treated at par with law-abiding project proponents. Doctrine of Public Trust: The State has a duty to protect natural resources for present and future generations. Implications of the Judgment: Reinforces the principle of prior environmental clearance as a non-negotiable legal requirement. Acts as a deterrent against regulatory bypass and upholds environmental governance. Places greater responsibility on the MoEF&CC, State Authorities, and Pollution Control Boards to ensure compliance with EIA norms. May affect projects that had earlier obtained post facto clearance between 2017–2021. Conclusion: The Supreme Court’s decision reaffirms India’s commitment to environmental protection and constitutional rights, rejecting a compliance regime that favours industrial interests at the cost of ecological integrity. The judgment sets a landmark precedent in Indian environmental jurisprudence, ensuring that development does not override the fundamental right to a clean environment. Decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of RBCs. Increased fragility and cell stiffness. Vascular blockage, causing pain and organ injury. Increased susceptibility to infections, anemia, and stroke. Past Illegal Allotments Invalid

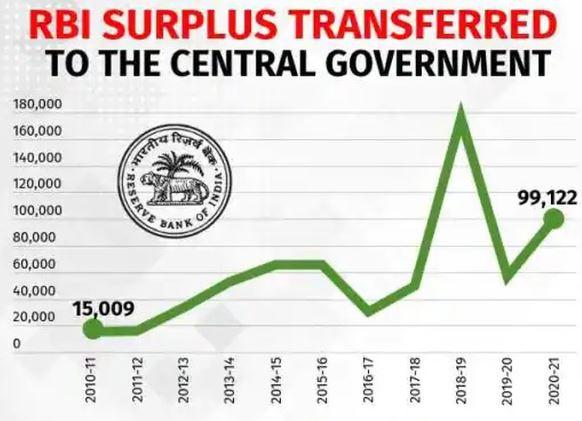

RBI ‘surplus’ transfer to the government

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 19th May 2025 Home / RBI ‘surplus’ transfer to the government Why in News? The RBI transfers its annual surplus to the central government based on the Economic Capital Framework, ensuring financial stability while supporting fiscal needs. Economic Capital Framework (ECF) The Economic Capital Framework (ECF) is a mechanism used by the RBI to determine how much risk provisioning it needs to maintain (to safeguard against potential financial shocks) and how much surplus (profit) it can transfer to the government. It ensures a balance between maintaining the RBI’s financial stability and meeting the fiscal needs of the government. Record Surplus Transfer in 2024-25 For the financial year 2024-25, the RBI is expected to transfer a record surplus in the range of Rs 2.5 lakh crore to Rs 3 lakh crore to the central government. This follows the highest-ever transfer of Rs 2.11 lakh crore in 2023-24. Although RBI doesn’t declare a “dividend” like commercial banks, it transfers the surplus (profits) to the government annually after meeting its reserve and operational requirements. How Does the RBI Earn Profits? The RBI earns income through the following operations: Foreign Currency Assets: The RBI invests in foreign currency assets like bonds, treasury bills of other central banks, and top-rated securities. The interest or returns earned from these are part of its income. Domestic Government Securities: It earns interest from its holdings of rupee-denominated government bonds and securities. Lending to Banks: It lends money to commercial banks for short durations (such as overnight) under liquidity adjustment facilities, earning interest in the process. Management Fees: It charges the central and state governments a fee for managing their borrowings. Expenditure:RBI’s main expenditures include: Printing and distribution of currency. Staff salaries and administrative expenses. Commissions paid to banks for government transactions and to primary dealers for underwriting bond issues. Legal Basis for Surplus Transfer According to Section 47 of the RBI Act, 1934, after making provisions for: Bad and doubtful debts Depreciation of assets Staff-related funds Other customary banking provisions …the remaining surplus is transferred to the Central Government. Does the RBI Pay Tax on its Profits? No. Under Section 48 of the RBI Act, 1934, the RBI is exempt from paying: Income tax Super-tax Wealth tax This exemption applies to all profits, income, or gains earned by the central bank. Is There a Fixed Policy for Surplus Distribution? There is no explicit policy, but various committees have guided the process: Malegam Committee (2013): Recommended higher surplus transfers to the government.After its recommendations, surplus transfer as a percentage of RBI’s gross income (less expenditure) rose significantly—from 53.40% in 2012-13 to 99.99% in 2013-14. Earlier, surplus was partly retained in: Contingency Fund (CF): For unforeseen financial emergencies. Asset Development Fund (ADF): For internal capital expenditure and investments in subsidiaries. These reserves were meant to maintain RBI’s financial resilience and credibility in times of crisis. Differences Between RBI and Government The Government of India has at times argued that the RBI holds excess reserves compared to global benchmarks and has suggested that the surplus could be used for purposes like recapitalising public sector banks. The RBI, on the other hand, has emphasized the need for large reserves to: Ensure financial stability Maintain market confidence Safeguard against macroeconomic and financial risks RBI views higher reserves as a critical element of its institutional independence. Despite these occasional differences, both sides usually reach a negotiated settlement, as noted by former RBI Governor Duvvuri Subbarao. How Do Other Central Banks Handle Surplus Transfers? United Kingdom and United States: The central bank and the government mutually decide the quantum of surplus transfer. Japan: The government unilaterally decides the amount of surplus transfer. On average, surplus transfers by central banks globally amount to around 0.5% of GDP, though this can vary by country and context. Decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of RBCs. Increased fragility and cell stiffness. Vascular blockage, causing pain and organ injury. Increased susceptibility to infections, anemia, and stroke. Past Illegal Allotments Invalid

What is a Presidential reference?

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 20th May 2025 Home / What is a Presidential reference? Why in News? President Droupadi Murmu has referred constitutional questions to the Supreme Court under Article 143 regarding the powers and timelines for Presidential and Gubernatorial assent to State Bills. Historical Context of Article 143 The advisory jurisdiction of the Supreme Court under Article 143 is rooted in colonial-era constitutional law: Government of India Act, 1935: It allowed the Governor-General to refer questions of law to the Federal Court for its opinion. This was intended to provide legal clarity on matters of governance and public interest. Adopted in Indian Constitution: Post-Independence, Article 143 was included to provide a non-binding advisory role to the Supreme Court on matters of law or fact of public importance, as advised by the Council of Ministers. Comparative Perspectives: Canada: Similar provision exists in the Canadian Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada can give advisory opinions on legal questions referred by federal or provincial governments. USA: The U.S. Supreme Court does not entertain advisory opinions, respecting the doctrine of strict separation of powers. Only actual “cases and controversies” are adjudicated. Provisions under Article 143 Article 143 – Advisory Jurisdiction It has two clauses: Article 143(1): The President may refer to the Supreme Court any question of law or fact of public importance for its opinion. Article 143(2): Specifically applies to disputes arising out of pre-constitutional treaties or agreements, mostly obsolete now. Article 145: Prescribes that a minimum five-judge bench hears such a reference. Nature of the Opinion: The opinion is not binding on the President or the executive. It does not create precedent for future cases, unlike judgments under Articles 32 or 136. However, it has high persuasive value and is generally respected and followed by both the executive and judiciary. Past Instances of Presidential References Since 1950, about 15 Presidential references have been made. Some important ones include: Case Year Significance Delhi Laws Act Case 1951 Laid down principles of delegated legislation. Kerala Education Bill 1958 Balanced Fundamental Rights vs Directive Principles; clarified minority rights under Article 30. Berubari Case 1960 Held that cession of territory requires constitutional amendment under Article 368. Keshav Singh Case 1965 Explained powers and privileges of State legislatures. Presidential Poll Reference 1974 Stated that elections can continue despite vacancies in State Assemblies. Special Courts Bill 1978 Established that the Court may decline vague references and must respect separation of powers. Cauvery Water Dispute 1992 Held that SC cannot sit in appeal over earlier judgments in advisory capacity. Third Judges Case 1998 Explained collegium system; laid down procedure for appointment of judges. Ram Janmabhoomi Reference 1993 Only instance where the Supreme Court declined to answer, citing lack of clarity and political sensitivity. The Current Reference (2024-25) Trigger for the Reference: The Supreme Court, in a recent judgment, set timelines for: The President and Governors to act on Bills passed by State legislatures. Held that their actions are justiciable and can be subject to judicial review. Government’s Concerns: The President, acting on the advice of the Union Cabinet, has referred 14 legal questions to the Supreme Court.These include: Can the court prescribe timelines for the President or Governors where the Constitution is silent? Is the President’s/Governor’s decision on a Bill justiciable before it becomes law? To what extent can the Supreme Court exercise powers under Article 142 (complete justice)? Whether the executive action during a pending Bill can be reviewed? Context of the Conflict: Increasing friction between the Union Government and Opposition-ruled State governments. Some Governors have delayed action on State Bills. SC criticized delays and adopted Home Ministry’s Office Memorandum to set a time limit. Objective of the Reference: To seek constitutional clarity on: The scope of judicial review over the President/Governor’s discretion. Whether courts can mandate timelines when none exist in the Constitution. Federal balance and coordination in a constitutional democracy. Importance of the Current Reference Clarification will determine: The boundaries of judicial intervention in executive discretion. The federal character of Indian polity. The principle of constitutional governance and accountability. The issue touches upon fundamental principles of: Separation of powers Democratic decision-making Judicial activism vs restraint Decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of RBCs. Increased fragility and cell stiffness. Vascular blockage, causing pain and organ injury. Increased susceptibility to infections, anemia, and stroke. Past Illegal Allotments Invalid