UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 14th July 2025

India’s Emissions Intensity Targets under the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS)

Why in News?

The Government of India has set emissions intensity targets for eight industrial sectors under the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS).

Introduction

In a significant move towards achieving its climate commitments, the Indian government recently notified greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity targets for entities operating within eight of the nine heavy industrial sectors under the compliance mechanism of India’s Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS). These sectors include:

- Aluminium, Cement, Paper and pulp, Chlor-alkali

- Iron and steel, Textile, Petrochemicals

- Petroleum refineries

This development marks an important milestone in India’s evolving climate policy architecture.

The Central Question: Where Should Ambition Be Measured?

- The evidence suggests that the most appropriate lens is the economy-wide aggregate level.

- Sector- or entity-level targets may appear modest or uneven, but what ultimately matters is whether the cumulative effect helps the country move toward its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and net-zero by 2070 goals.

Lessons from the PAT Scheme

India’s Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme, launched in 2012, is the country’s flagship market-based mechanism for improving energy efficiency in large industrial units. Under PAT, energy-intensive sectors receive reduction targets; those that outperform can trade Energy Saving Certificates (ESCerts) with underperformers.

Key observations from PAT Cycle I (2012–14):

- Mixed results at the entity and sector levels:

- Energy intensity rose in paper and chlor-alkali sectors.

- It fell in the aluminium and cement sectors.

- However, overall energy use per unit of economic output declined, demonstrating an aggregate improvement in energy efficiency.

- Insight:

Even when some entities or sectors underperform, a well-functioning market mechanism can lead to economy-wide efficiency gains. This reinforces the idea that assessing ambition at the aggregate level is more meaningful than disaggregated assessments.

Why Sectoral or Entity-Level Comparisons Are Not Enough

Several arguments explain why sector/entity-level comparisons are not sufficient:

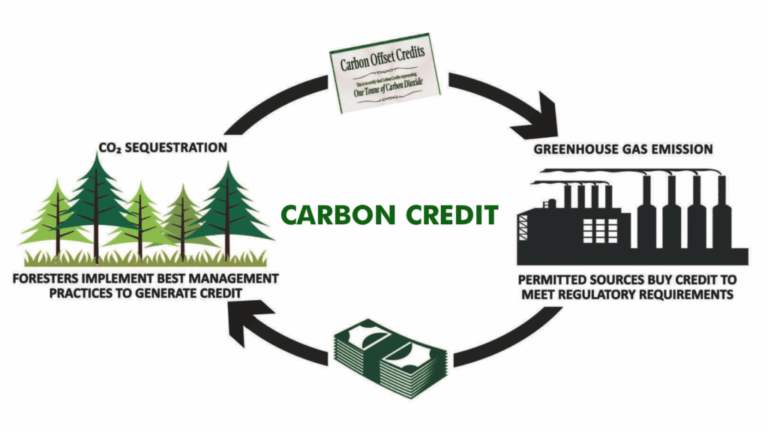

- Market mechanisms equalise cost across entities: Firms that find it expensive to reduce emissions internally can purchase credits, ensuring cost-effective compliance. This does not reduce aggregate ambition but redistributes the burden efficiently.

- Historical performance is not a benchmark for future ambition: Comparing new targets with past sectoral performance (e.g., under PAT) may be misleading. Ambition must progressively increase to stay on track for long-term decarbonisation goals.

- Only economy-wide modelling reveals true alignment with climate goals: Directly comparing sectoral CCTS targets to India’s NDC is problematic because:

- CCTS targets cover only a part of India’s total industry.

- NDCs are economy-wide and include multiple sectors such as agriculture, buildings, and transport.

Are the CCTS Targets Ambitious Enough?

According to recent economy-wide modelling aligned with India’s 2030 NDC targets, the findings are as follows:

Projected Decline in Emissions Intensity (2025–2030):

- India’s Energy Sector (CO₂ intensity per unit of GDP): Decline at 3.44% annually

- India’s Manufacturing Sector (EIVA – Emissions Intensity of Value Added): Decline at 2.53% annually

- Combined Annual EIVA Reduction Based on Current CCTS Targets (2023–2027): Only 1.68% annually

What This Means:

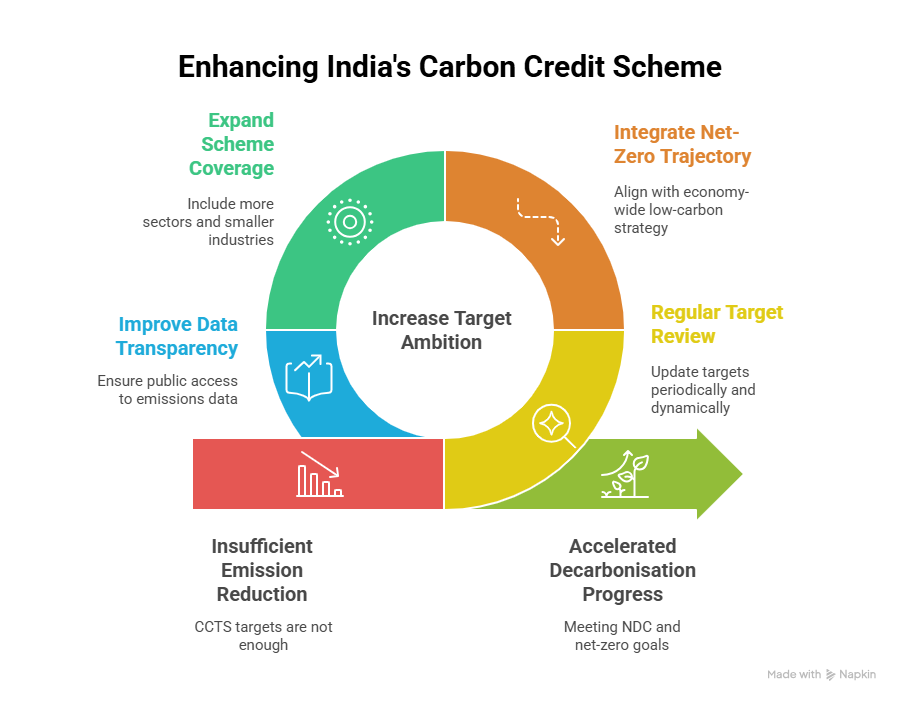

- The CCTS targets are falling short of the pace required to align with a net-zero pathway.

- The industry sector is decarbonising more slowly than other sectors like power, where low-cost mitigation opportunities (e.g., renewable energy) are more abundant.

- The current industrial targets under CCTS, while a positive step, may not be ambitious enough to drive a rapid, transformative shift.

Implications for Policy and Climate Action

- Need for Regular Review and Revision: CCTS targets should be dynamic and updated periodically to reflect new technological developments and global best practices.

- Integration with India’s Net-Zero Trajectory: The industrial sector’s emissions pathway must be aligned with the economy-wide low-carbon growth strategy.

- Expansion of Coverage: Eventually, CCTS must include more sectors and smaller industries to widen the impact.

- Transparency and Data Availability: Public access to data on emission baselines, verification, and trading volumes is critical for building trust and enabling effective monitoring.

Conclusion

- India’s Carbon Credit Trading Scheme is a significant policy innovation aimed at promoting cost-effective decarbonisation.

- However, assessing the ambition of its emissions intensity targets requires a macro-level perspective, focusing on aggregate outcomes rather than fragmented sectoral performances.

- Early estimates suggest that the current targets may not be sufficiently aggressive, especially when compared with the trajectories needed to meet India’s 2030 NDC and 2070 net-zero commitments.

- Going forward, more ambitious and adaptive targets, backed by rigorous economy-wide modelling, will be essential to ensure India’s carbon market fulfils its transformative potential.

3rd UN conference on landlocked countries

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / 3rd UN conference on landlocked countries Why in News? At the

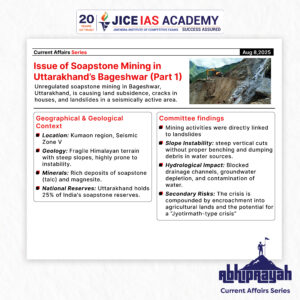

Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar Why in News? Unregulated

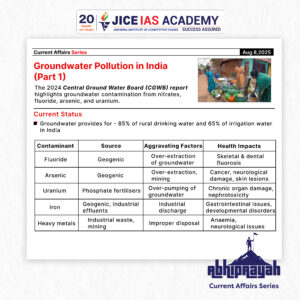

Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency Why

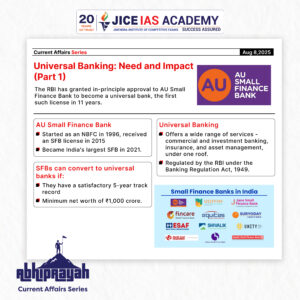

Universal banking- need and impact

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Universal banking- need and impact Why in News? The Reserve Bank

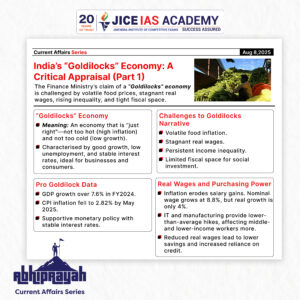

India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal Why in News? The Finance

U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from Russia

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from

Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology Why in

New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram Why in

Economic Implications

For Indian Exporters

- These reforms reduce transaction costs and compliance hurdles

- Encourage a more competitive and efficient export environment

- Promote value addition in key sectors like leather

For Tamil Nadu

- The reforms particularly benefit the state’s leather industry, a major contributor to employment and exports

- Boost the marketability of GI-tagged E.I. leather, enhancing rural and traditional industries

For Trade Policy

- These decisions indicate a shift from regulatory controls to policy facilitation

Reinforce the goals of Make in India, Atmanirbhar Bharat, and India’s ambition to become a leading export power

Recently, BVR Subrahmanyam, CEO of NITI Aayog, claimed that India has overtaken Japan to become the fourth-largest economy in the world, citing data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

India’s rank as the world’s largest economy varies by measure—nominal GDP or purchasing power parity (PPP)—each with key implications for economic analysis.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!