UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 30th July 2025

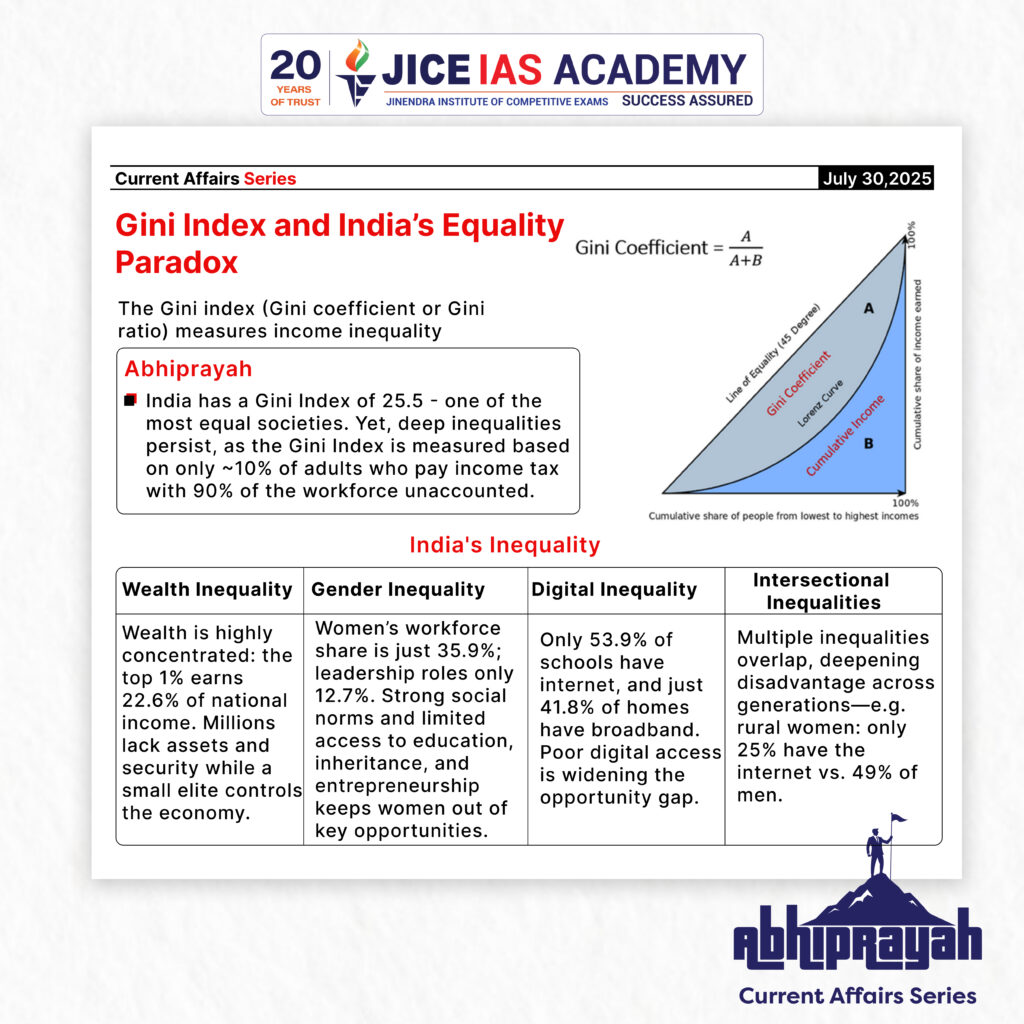

Gini Index and India’s Equality Paradox

Why in News?

- Despite being ranked among the world’s most equal societies by the Gini Index, India continues to grapple with deep-rooted economic, gender, digital, and educational inequalities.

Introduction

- The Gini Index has recently ranked India among the world’s most equal societies, assigning it a score of 5.

- This places India in the category of moderately low inequality, an assessment that, on the surface, may seem like an achievement worthy of celebration.

- However, when juxtaposed with the lived experiences of millions across India’s urban and rural landscapes, this statistical portrayal appears disconnected from reality.

- Despite the Gini Index’s implications of relative equality, Indian society remains deeply fractured by structural, economic, social, gender, and technological inequalities.

- These inequalities manifest not only in hard data but also in the everyday experiences of people, suggesting that equality on paper does not translate to equality in practice.

Questioning the Gini Index: Methodological Limitations

- The Gini Index calculates inequality based primarily on income distribution, relying heavily on tax data.

- However, this methodology poses a fundamental limitation in the Indian context.

- A significant portion of India’s workforce is engaged in the informal sector, which remains outside the tax net.

- In fact, only around 10% of the adult population contributes to tax data used in such measurements.

- This limitation means that a large segment of the population — especially those earning below taxable thresholds or engaged in informal employment — is excluded from statistical measurement, leading to underreporting of real income disparities.

- Consequently, the apparent equality suggested by the Gini Index may be less a reflection of reality and more a by-product of flawed measurement.

Wealth Inequality:

- One of the most glaring forms of inequality in India is wealth inequality.

- This is vividly illustrated by everyday scenes in Indian cities: a chauffeur earning ₹3 lakh annually drives a luxury car worth ₹30 lakh owned by a wealthy employer.

- This example illustrates how wealth is concentrated in the hands of a few, while a vast population struggles to meet basic needs.

- The ‘Income and Wealth Inequality in India, 1922–2023’ report highlights that in 2022–23, the top 1% of India’s population earned 22.6% of the national income.

- This concentration of wealth among the elite, combined with poor formal employment opportunities and low wage levels, indicates a deep-rooted structural imbalance.

- The lack of wealth data itself becomes a reflection of inequality, as those earning below the taxable threshold — often the poorest — are statistically invisible.

Gender Inequality:

- Gender inequality in India continues to be a major obstacle to social justice and economic development.

- Women remain underrepresented in the workforce, with only 9% participation, and this figure drops dramatically at leadership levels — only 12.7% of leadership positions were held by women in 2024.

- Even in India’s thriving startup ecosystem, which is the third largest in the world, women-led ventures account for a mere 5% of active startups.

- Traditional social norms restrict women’s access to family resources, education, and inheritance, further limiting their upward mobility.

- Thus, gender inequality is not only a product of economic exclusion but also of entrenched social norms and cultural practices.

Digital Inequality:

- As technology becomes increasingly essential to daily life — enabling access to banking, education, employment, and governance — digital inequality emerges as a critical concern.

- Despite improvements in digital infrastructure, access remains highly unequal.

- For instance, only 7% of schools in India have functional computers, and 53.9% have Internet connectivity.

- This digital gap severely affects students from marginalized socio-economic backgrounds, who are denied critical digital skills necessary for higher education and jobs.

- The digital divide also intersects with educational inequality. When schools switch to virtual modes, such as during periods of high pollution in Delhi, only students with broadband access — just 8% of households — can continue learning.

- Those without access are pushed into low-skill jobs, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and exclusion.

Intersecting Inequalities

- Inequality in one area often exacerbates inequality in another. This phenomenon is especially evident when analyzing intersectional inequalities — the combined effect of multiple forms of disadvantage.

- For example, digital inequality disproportionately affects women, especially in rural areas. Only 25% of rural women have Internet access compared to 49% of rural men.

- The Internet is not just a tool for information — it is a gateway to empowerment. It facilitates access to financial services, job markets, education, and government schemes.

- Women who lack access to the Internet are systematically denied these opportunities, deepening both digital and gender inequalities.

A Reality Check: Are We Truly an Equal Society?

- While international rankings may suggest that India is moving towards greater equality, these rankings must be interpreted with caution. The reality on the ground tells a different story.

- For a society to be genuinely equal, it must ensure equal access to opportunities, resources, and decision-making power for all its citizens.

- The existing forms of inequality — wealth, gender, educational, and digital — continue to intersect and reinforce each other, keeping large sections of the population trapped in poverty and exclusion.

- Unless these foundational inequalities are addressed, statistical claims of equality will remain hollow.

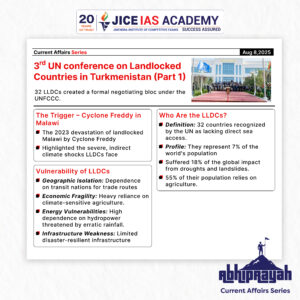

3rd UN conference on landlocked countries

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / 3rd UN conference on landlocked countries Why in News? At the

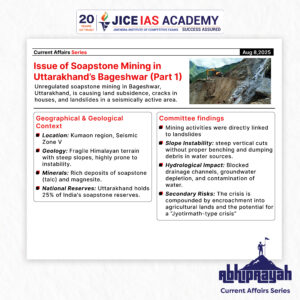

Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar Why in News? Unregulated

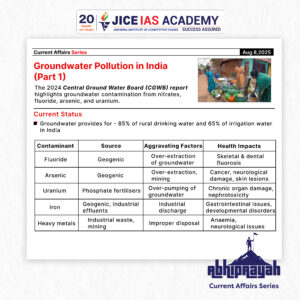

Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency Why

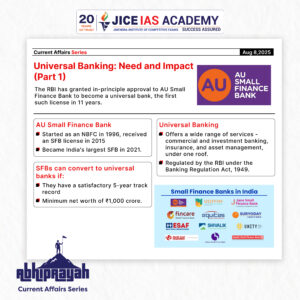

Universal banking- need and impact

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Universal banking- need and impact Why in News? The Reserve Bank

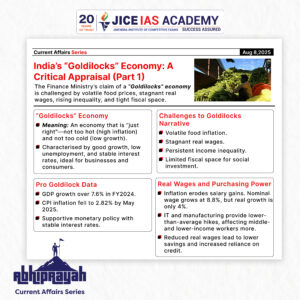

India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal Why in News? The Finance

U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from Russia

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from

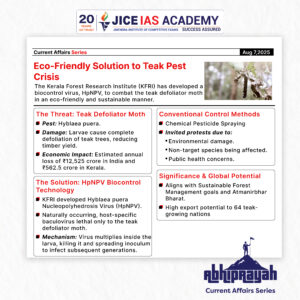

Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology Why in

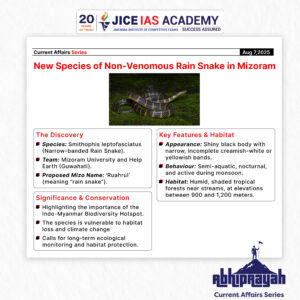

New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram Why in

Introduction

Economic Implications

For Indian Exporters

- These reforms reduce transaction costs and compliance hurdles

- Encourage a more competitive and efficient export environment

- Promote value addition in key sectors like leather

For Tamil Nadu

- The reforms particularly benefit the state’s leather industry, a major contributor to employment and exports

- Boost the marketability of GI-tagged E.I. leather, enhancing rural and traditional industries

For Trade Policy

- These decisions indicate a shift from regulatory controls to policy facilitation

Reinforce the goals of Make in India, Atmanirbhar Bharat, and India’s ambition to become a leading export power

Recently, BVR Subrahmanyam, CEO of NITI Aayog, claimed that India has overtaken Japan to become the fourth-largest economy in the world, citing data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

India’s rank as the world’s largest economy varies by measure—nominal GDP or purchasing power parity (PPP)—each with key implications for economic analysis.