UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 04th August 2025

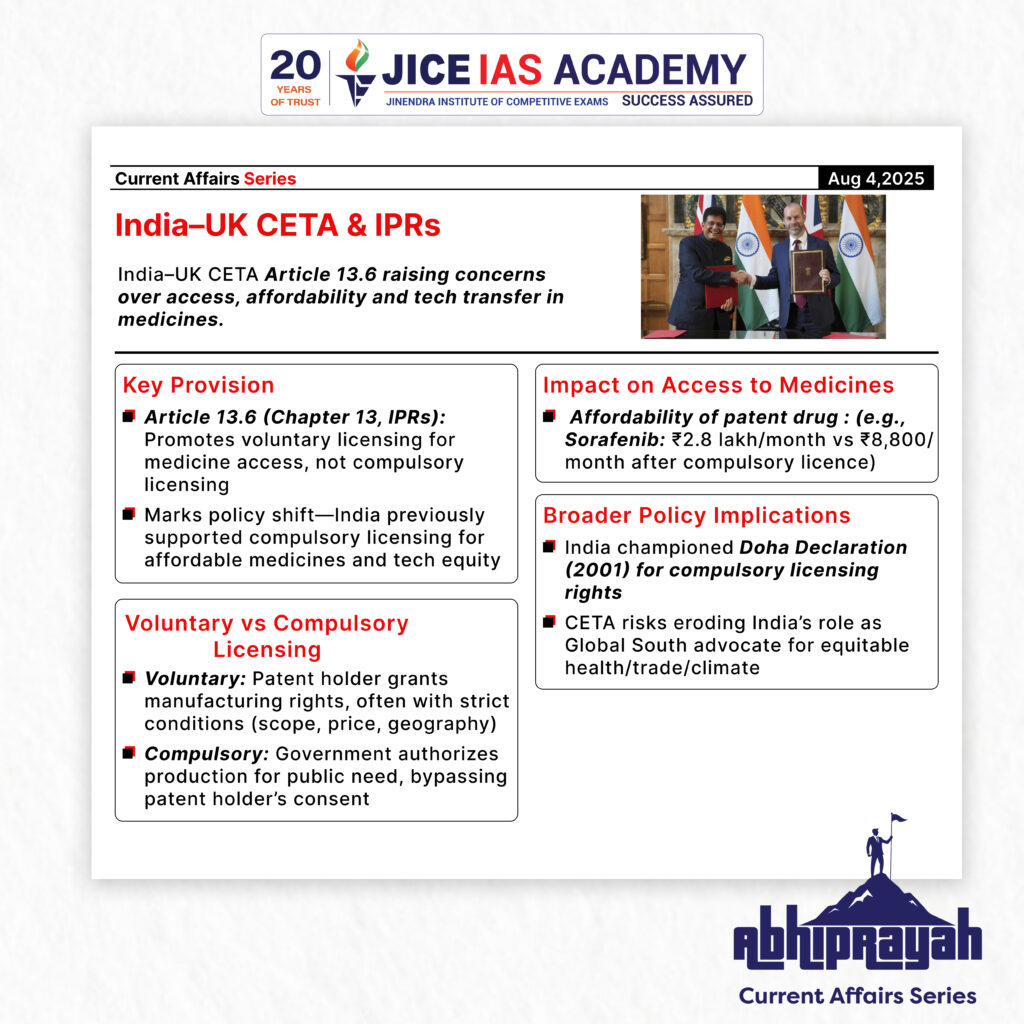

India-UK Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and Its Implications on Intellectual Property Rights

Why in News?

- India–UK CETA’s Article 13.6 may undermine India’s long-standing support for compulsory licensing and equitable technology transfer by prioritising voluntary mechanisms.

Introduction

- The India–United Kingdom Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), particularly Chapter 13 on Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), has sparked concerns about India’s shift in policy related to public health safeguards and technology access.

- A contentious clause in this chapter — Article 13.6, titled “Understandings Regarding TRIPS and Public Health Measures” — has significant implications for India’s established position on compulsory licensing and technology transfer.

Key Provision: Article 13.6 of CETA

- The Parties recognise the preferable and optimal route to promote and ensure access to medicines is through voluntary mechanisms, such as voluntary licensing which may include technology transfer on mutually agreed terms.

Implications

- This clause suggests that both countries prefer voluntary licensing over compulsory licensing as a method for ensuring access to medicines.

- This represents a significant departure from India’s historical stance, which has consistently advocated compulsory licensing to make essential medicines more affordable, especially for lower-income populations.

Impact on Access to Affordable Medicines

High Costs of Patented Medicines

- One of the fundamental flaws in the global patent regime is the high cost of patented medicines, resulting from the monopolistic pricing strategies of pharmaceutical corporations. In India, a notable case is the anti-cancer drug Sorafenib Tosylate, originally priced at over ₹2.8 lakh per month by Bayer Corporation.

- In 2012, a compulsory licence was granted to Natco Pharma, allowing the drug to be sold at around ₹8,800 per month — a reduction of over 90 percent.

Compulsory Licensing in Indian Law

- India amended its Patents Act, 1970 to comply with the WTO’s Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), incorporating important public health safeguards such as compulsory licensing under Section 84.

- This provision allows licences to be granted three years after the grant of a patent if:

- The public’s reasonable requirements are not being met,

- The patented product is not available at a reasonable price,

- The patent is not “worked” (commercially used) in India.

These provisions were adopted unanimously by both Houses of Parliament after being examined by a Joint Parliamentary Committee.

Dilution Through Free Trade Agreements

- In its earlier agreement with the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), India diluted the requirement for annual reporting of a patent’s “working status” to once every three years.

- This limits the information available to determine if a compulsory licence should be issued.

- The India–UK CETA reaffirms this dilution, thereby undermining a key legal basis for issuing such licences.

Voluntary Licensing versus Compulsory Licensing

- Voluntary licensing refers to the patent holder granting permission to another party to manufacture and sell the patented product, usually under strict conditions.

- In contrast, compulsory licensing allows governments to authorize such production without the consent of the patent holder under specific conditions.

- Voluntary licences are problematic because:

- They are often lismited in scope and geography.

- Patent holders retain control over key elements such as supply chains.

- Local producers are placed at a disadvantage during negotiations.

- The humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has pointed out that voluntary licensing allows multinational pharmaceutical companies to control access by setting restrictive terms.

- For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Cipla produced Remdesivir under a voluntary licence from Gilead Sciences.

- However, the price in India was higher in purchasing power terms than what Gilead charged in the United States, highlighting the ineffectiveness of voluntary licensing in ensuring affordable access.

Impact on Technology Transfer and Climate Commitments

- In 1974, through the United Nations General Assembly, developing countries including India demanded a New International Economic Order (NIEO).

- A key component was the transfer of technology from developed to developing countries on favourable terms to support industrial development and self-reliance.

India’s Position in Climate Forums

- In multilateral climate negotiations, India has repeatedly emphasised the need for equitable technology transfer, especially in the context of reducing carbon emissions.

- India’s Fourth Biennial Update Report (2024) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) stated that:

- Despite substantial national efforts and investments, barriers like slow international technology transfer and intellectual property rights (IPR) hinder the rapid adoption of climate friendly technologies.

- By accepting terms in CETA that imply technology transfer should be negotiated “on mutually agreed terms” rather than being mandatory or on favourable terms, India weakens its case in demanding affordable and accessible green technologies from developed nations.

Broader Policy Implications

India’s Role in the Doha Declaration

- India played a pivotal role in securing the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health (2001), which reaffirmed the right of countries to issue compulsory licences and determine the grounds for such issuance.

- The Declaration strengthened the legal basis for developing countries to override patent rights in the interest of public health.

Erosion of Leadership in Global South Advocacy

- India has traditionally been a leader in defending the rights of developing countries in global intellectual property forums.

- The provisions of CETA may erode this position, weakening India’s ability to push for equitable trade, health, and environmental outcomes in future negotiations.

3rd UN conference on landlocked countries

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / 3rd UN conference on landlocked countries Why in News? At the

Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Issue of soapstone mining in Uttarakhand’s Bageshwar Why in News? Unregulated

Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Groundwater Pollution in India – A Silent Public Health Emergency Why

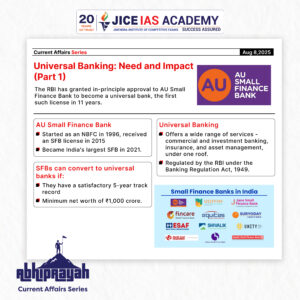

Universal banking- need and impact

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / Universal banking- need and impact Why in News? The Reserve Bank

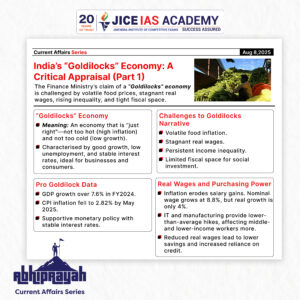

India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 08th August 2025 Home / India’s “Goldilocks” Economy: A Critical Appraisal Why in News? The Finance

U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from Russia

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / U.S.-India Trade Dispute: Trump’s 50% Tariffs and India’s Oil Imports from

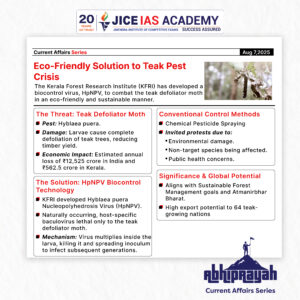

Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / Eco-Friendly Solution to Teak Pest Crisis: KFRI’s HpNPV Technology Why in

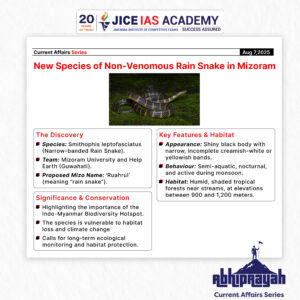

New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram

UPSC CURRENT AFFAIRS – 07th August 2025 Home / New Species of Non-Venomous Rain Snake Discovered in Mizoram Why in

Introduction

Economic Implications

For Indian Exporters

- These reforms reduce transaction costs and compliance hurdles

- Encourage a more competitive and efficient export environment

- Promote value addition in key sectors like leather

For Tamil Nadu

- The reforms particularly benefit the state’s leather industry, a major contributor to employment and exports

- Boost the marketability of GI-tagged E.I. leather, enhancing rural and traditional industries

For Trade Policy

- These decisions indicate a shift from regulatory controls to policy facilitation

Reinforce the goals of Make in India, Atmanirbhar Bharat, and India’s ambition to become a leading export power

Recently, BVR Subrahmanyam, CEO of NITI Aayog, claimed that India has overtaken Japan to become the fourth-largest economy in the world, citing data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

India’s rank as the world’s largest economy varies by measure—nominal GDP or purchasing power parity (PPP)—each with key implications for economic analysis.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.